Presenting Chris Day - Craft Spotlight at Harewood House | FT Feature by Jenny Elliott

14th July 2021

Chris Day — glassblower who tackles a stained colonial history | Jenny Elliot for the Financial Times

Vessel Gallery presents Chris Day, Britain’s only black glass artist, who has created an exhibition within the grounds of Harewood House to reflect the history of the place. All works on show have been curated by Vessel Gallery’s creative director, Angel Monzon.

Chris Day with 'Message in a Bottle' and header image © Charlotte Graham

A surprising congregation sits in All Saints Church, on the grounds of stately home Harewood House in West Yorkshire: 13 irregular dark glass orbs in heavy terracotta bowls, shown on a white platform atop Victorian pews. Each piece is distinct, but what the group shares is how their fragile, translucent skins bulge and curve from being blown through copper wire cages — like chains cutting into flesh.

It is easy to be drawn to the iridescent quality of Chris Day’s mixed media art, but there is no question that the work, “The Congregation” (2021), tells of brutality. Here Day depicts enslaved people being marshalled to church on their day off. “It wasn’t their religion,” says Day. “On the other hand, at church they could sit down, have a break from plantation work.”

Day is of mixed-race descent: his father is Jamaican, his mother is Anglo-Irish. Growing up on a council estate in a predominantly white area of Derby in the Midlands, he talks about his happy childhood, yet he’s aware that his outsider status impacted his self-worth. “These experiences have led me here,” says Day, speaking in the church. “But it’s a hard thing to let everyone know who you are. I’ve hidden that for such a long time.”

Dark, earthy glass globules: ‘Strange Fruit’ installation © Tom Arber

For 20-odd years, Day worked as a plumber and heating engineer. Then in 2016, when he was 48, his wife persuaded him to follow his childhood passion and enrol in a bachelors degree in glass and ceramics at the University of Wolverhampton. Although glassblowing is now integral to his art, at first he avoided it. “I had my self-employment head on,” Day says. “I kept thinking: how can I make a business out of this? How can I get a furnace in my garage?”

Following a compulsory glass module, though, Day was converted; he loved the warmth of the hot shop and the thrill of working with unpredictable material. Not that he’s interested in creating flawless glassware. He describes his process as physical and fluid, like sketching with materials.

In the early days of his BA, Day began researching the history of slavery and racial oppression in the US and UK. He felt compelled to amplify this history and reflect on his own heritage, so he created “Commodity Triptych” (2019), black glass “heads” crammed into three crates stencilled with “Property of British Sugar”, about the dehumanising impact of the slave trade, and “Strange Fruit” (2019), dark, earthy glass globules dangling from hessian cord and meat hooks, inspired by the 1937 poem about lynchings in America’s Deep South.

'Commodity Triptych’ © Tom Arber

Both artworks feature in Day’s exhibition at Harewood. “Strange Fruit” is accompanied by Billie Holiday’s musical version of the poem, her rich, mournful voice intertwining with the birdsong outside. “I’m not trying to change people’s perceptions of what happened in the past,” says Day. “I’m just telling you. I’m just a storyteller.”

Day’s art, which is already in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, drew the eye of Hannah Obee, director of collections, programme and learning at Harewood House Trust, when she was developing a new “Craft Spotlight” series. Startled by a 2018 Crafts Council report, which said that 96 per cent of professional, full-time craftspeople identified as white (compared with 88 per cent across all occupations), the trust was keen to address the underrepresentation of makers of diverse heritage. “We also wanted to find a way of opening difficult conversations around colonial history,” says Obee.

Harewood House is part of those conversations: it stands on land bought by Henry Lascelles in 1738 using a fortune from the West Indian sugar industry built on the transatlantic slave trade. These profits were later used by his son, Edwin Lascelles, to build and furnish the house. Following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, the trust renewed its commitment to interrogate its past and has developed a broad-based “Open History” programme to involve visitors in this dialogue.

For Day, the chance to exhibit at Harewood House, especially in its church, was ideal. The light-dappled space with its alabaster tombs and mottled sandstone provides a contrasting surrounding to Day’s chilling art. Day also likes the symbolism: “I don’t think people realise how dirty the fingers of the church were when it came to slavery.”

‘Under the Influence’ Detail © Tom Arber

“Message in a Bottle” (2021) and “Under the Influence” (2021) have both been created for the exhibition and feature large, handblown bottles. Day says he was already experimenting with vessel shapes when he learnt that 28 bottles of rum from the Lascelles’s plantations had been discovered in Harewood’s cellar in 2011 and, at auction, had become the world’s most expensive. (The proceeds were donated to the Geraldine Connor Foundation, which supports British Caribbean communities.) Everything clicked for Day.

His syrup-brown bottle sculptures, swirled in royal blue to evoke the sea crossings, provide a reminder of the importance of rum in the slave trade. The 10 bottles in “Under the Influence”, each unique and with a braided stopper to suggest being bound, are positioned under Edwin Lascelles’s memorial plaque, highlighting the power of the plantation owners and the influence of the slave trade on society’s structures.

Although he’s thought to be Britain’s only black glassblower, it’s a title Day is keen to lose. He hopes his own example will encourage young people from diverse backgrounds into craft practice. As the sun cuts through the church’s vibrant stained-glass windows and falls on his own glasswork, Day reflects on the importance of representation and hearing a range of narratives. “These stained-glass windows are telling a story, and I’m doing exactly the same. Same material. Different era,” says Day. “Still just telling stories.”

To 31 October 2021, www.harewood.org

‘Under the Influence’ © Charlotte Graham

'Message in a Bottle' Detail © Tom Arber

'The Congregation' Detail © Tom Arber

About Harewood House

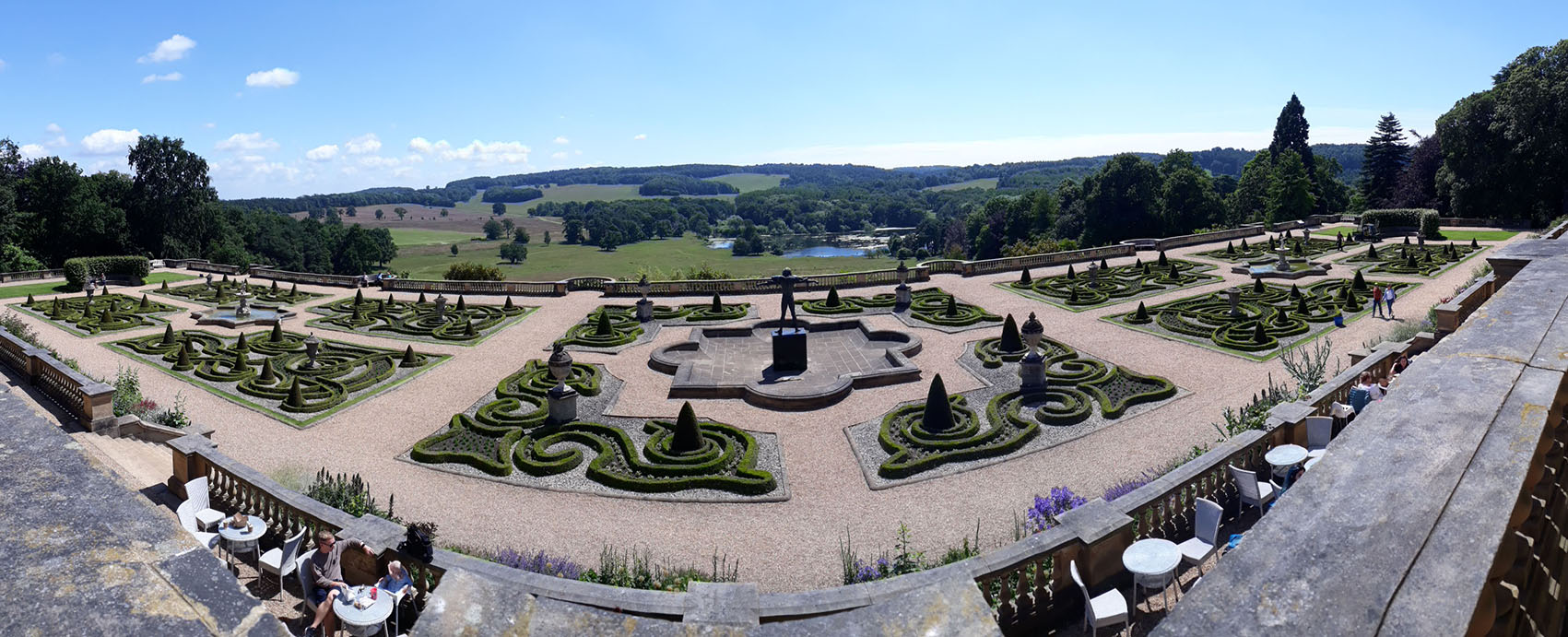

Harewood sits in the heart of Yorkshire and is one of the Treasure Houses of England. The House was built in the 18th century and has art collections to rival the finest in Britain. The estate (now managed by a trust) offers exhibitions of contemporary art, the rare Bird Garden and Farm Experience plus over 100 acres of exquisite gardens to explore. Built with riches made from the slave trade, you can read more about the foundation of Harewood House in relation to the sugar cane industry here

"Harewood’s history is still evolving – always changing, always striving to stay relevant to the present day. It must be alive, cared for by the people who inhabit it and enjoyed by the people who visit it. Harewood is a living history, one with many stories still to tell. I believe very strongly that we can change things in the present, but for better or for worse there is nothing that any of us can do about history and the past"

David Lascelles, Earl of Harewood

© Juliet Mayo

© Juliet Mayo