Jon Lewis - Distant Electric Vision | An essay by Emma Park

1st February 2022

Jon Lewis - Distant Electric Vision | An essay by Emma Park

If an artist’s studio reflects his personality, then Jon Lewis might be an eccentric inventor as much as a glassblower. In his workshop in Parndon Mill, a community of makers in Harlow, Essex, the cupboard doors are papered with enigmatic lists and diagrams, while inside there are trays piled high with drills, diamond-tipped polishers and obscure parts of machines. Wicker baskets hang next to wire mesh on hooks jutting from the roof beams. Boxes of Kugler colours are stacked on top of an old chest. Between the windows, shelves nailed into the whitewashed brick wall display a cabinet of curiosities: glass vessels in various shapes and colours, a wooden letter ‘M’ wrapped in tinfoil, and a steel winch attached to a glass bulb. A cactus, a toy truck and a stained glass panel sit side by side on a windowsill. In a dark corner, a tall steel rod that has been hacked into by an angle grinder stands on its end like a worm-eaten apple core.

![]()

The artist’s studio

In the garden outside the studio is a large “automatic grinding machine”, as Lewis calls it, which he made himself from a marine winch gearbox and some pallet trunk rollers, and which he uses for polishing. One of his most striking characteristics as a glassmaker is just this element of resourcefulness: he has adapted or made much of his own equipment, including even a glory hole and a furnace, in the service of his distinctive aesthetic. This aesthetic, combining the machine & hand-made, cold metal and warm glass, takes centre stage at his first solo exhibition with Vessel Gallery.

Lewis’s most ambitious collection to date is Apertura, a series of glass sculptures, coated in iron ore, in the shape of tall standing stones; he called the earliest Monoliths. In each sculpture, two panels of glass on opposite sides, usually oblongs, have been left free of iron: these are the ‘apertures’, reminiscent of windows or screens. One of the works in this series, Apertura Aurora, won the Glass Society Award at the British Glass Biennale 2019. It contains two large panes of thick transparent glass, half-stained with purple, which encourage the viewer to look at or through them, into the sculpture and out the other side at a world distorted by the double refraction of light. The purple of the apertures is complemented and enhanced by the reddish rust of the iron coating.

“These vessels try to capture and frame a small plane of glass and colour,” says Lewis. “Sometimes, a small rectangle of handmade glass is just beautiful on its own.” The individual appeal of the glass is enhanced by the variation & graduation in the colours with which each piece is stained. Lewis even deliberately leaves a few bubbles in order to echo the texture of medieval glass. This detail goes back to the first five years of his career, when he made stained glass windows.

The glass in the Apertura series is made from the screen fronts of Bang & Olufsen Beovision 1 television sets that were, according to Lewis, top-of-the range when they came out in the early 2000s. These are made of a grey, very lead-rich glass with a high refractive index that makes it sparkle. At the same time, this type of glass was made to be pressed into a mould, so it is viscous and resistant to blowing.

To make an Apertura sculpture, Lewis first melts the television glass and blows it into the desired shape. He then applies an angle grinder to an iron core to generate a continuous shower of sparks whose heat allows them to be impregnated into the surface of the glass. He realised that iron sparks could be used in this way from a chance discussion with a friend, who described how he had accidentally fused iron onto a window he was installing. The iron that Lewis uses is all scrap metal, including metal frames from the salvaged televisions. The process, he says, feels rather “industrial”: he has to don a mask, earphones, a hat and leather jacket. “The whole place gets covered in metal.” The iron layer is substantial enough that magnets will stick to it – not something you would expect of glass.

![]()

Showering an artwork with iron, a process the artist called ‘spark impregnation’

Once the glass is coated with iron, except for the two ‘apertures’, he further patinates it by applying home-made ‘rubs’ of wine and chilli sauce, salt and coffee grains. He then leaves the sculpture outside where it will be exposed to the elements and where the ‘rub’ will speed up the process of patination. This stage could take anything from a couple of hours to years, depending on the depth and colouring of the texture that he wants to achieve. At the end, he will seal the patina with a layer of matt varnish to preserve it.

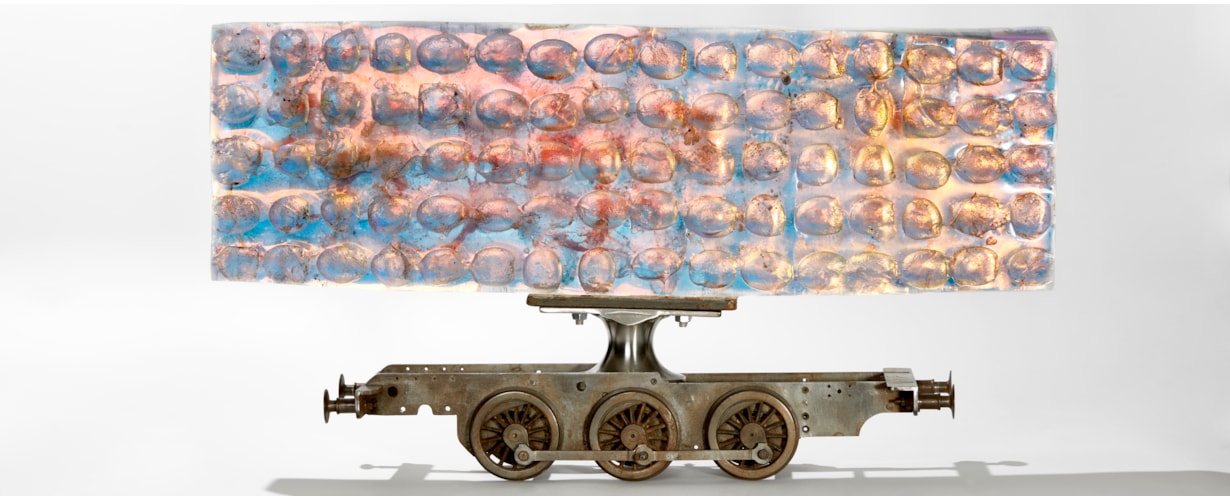

![]()

Transceiver, 2021

Another work from the Apertura series, Transceiver, refers more explicitly to the idea of the television. Transceiver consists of two ovoid glass sculptures, one taller and rustier, one shorter and more ashen in colour, extending upwards into tapering cones reminiscent of aerials. The plinths on which they stand are hollowed out, so as to suggest a sort of channel between them. It is as though they were transmitting ethereal messages above and below ground, to be displayed on the long, thin screens of graduated purple glass fading to yellow, while the screens themselves seem to turn away from each other, like two strange beings trapped inside the hard, impersonal casing and unable to communicate directly. In the twenty-first century, says Lewis, “we seem to look at life through a screen.” The pair of sculptures conjure up a sense of claustrophobia and isolation.

Transceiver received an honourable mention in the Glass Art Society’s 2021 exhibition Trace, which highlighted works that explored ideas of sustainability & ‘green’ glassmaking. Lewis, who was born in 1967, derives his artistic use of recycled materials from his childhood in the Malvern Hills, when he used to dig up pieces of Victorian glass and pottery from a bottle tip on a nearby farm. “That’s all that’s left from the Victorian age…glass and ceramics survive where nothing else would.” For similar reasons, glass is an ideal material not only for recycling, but for art about recycling; more clearly than most media, it embodies the process of taking one form and changing it into another. “I’d been recycling glass bottles and all sorts of things over the years,” he says. The idea of using television glass specifically came to him after a project with a friend where they used waste glass from a company that recycled televisions, which had turned a “weird, stony green colour”, to make stained glass windows.

‘Distant Electric Vision’, the title of the exhibition, is a phrase that was first used in 1908 by the engineer A.A.Campbell Swinton, who presciently described the principles of the television years before the technology existed to make one. The title alludes to the fusion of prehistoric and futuristic themes in works like the Apertura series, with their enclosure of modern TV glass within primitive iron ore.

The reference to Campbell Swinton also goes back to Lewis’s early training in electronics and computing, which he began after he left school at sixteen. At eighteen, however, he contracted glandular fever, and was out of action for six months. It was this illness which led to his decision to change direction and enrol at Hereford Art College for a year. Still unsure what to specialise in, he was leafing through a copy of his mother’s Lady magazine in an idle moment when he came across a feature about a glassblower who made perfume bottles. He was fascinated, and immediately applied to Wolverhampton University to do a BA in glass. This took him four years, from 1989-1993, including a year’s practical training at the former International Glass Centre at Brierley Hill, Stourbridge. At Wolverhampton, he made coldworked glass arrowheads, inspired by prehistoric flint tools; this was an early foray into the theme of glass as something ancient that can be found in the earth. This theme is continued in another series, Meteorites, which balances rusty surfaces with spirals of colour, juxtaposing what he calls ‘machine life’ with the suggestion of organic matter and DNA.

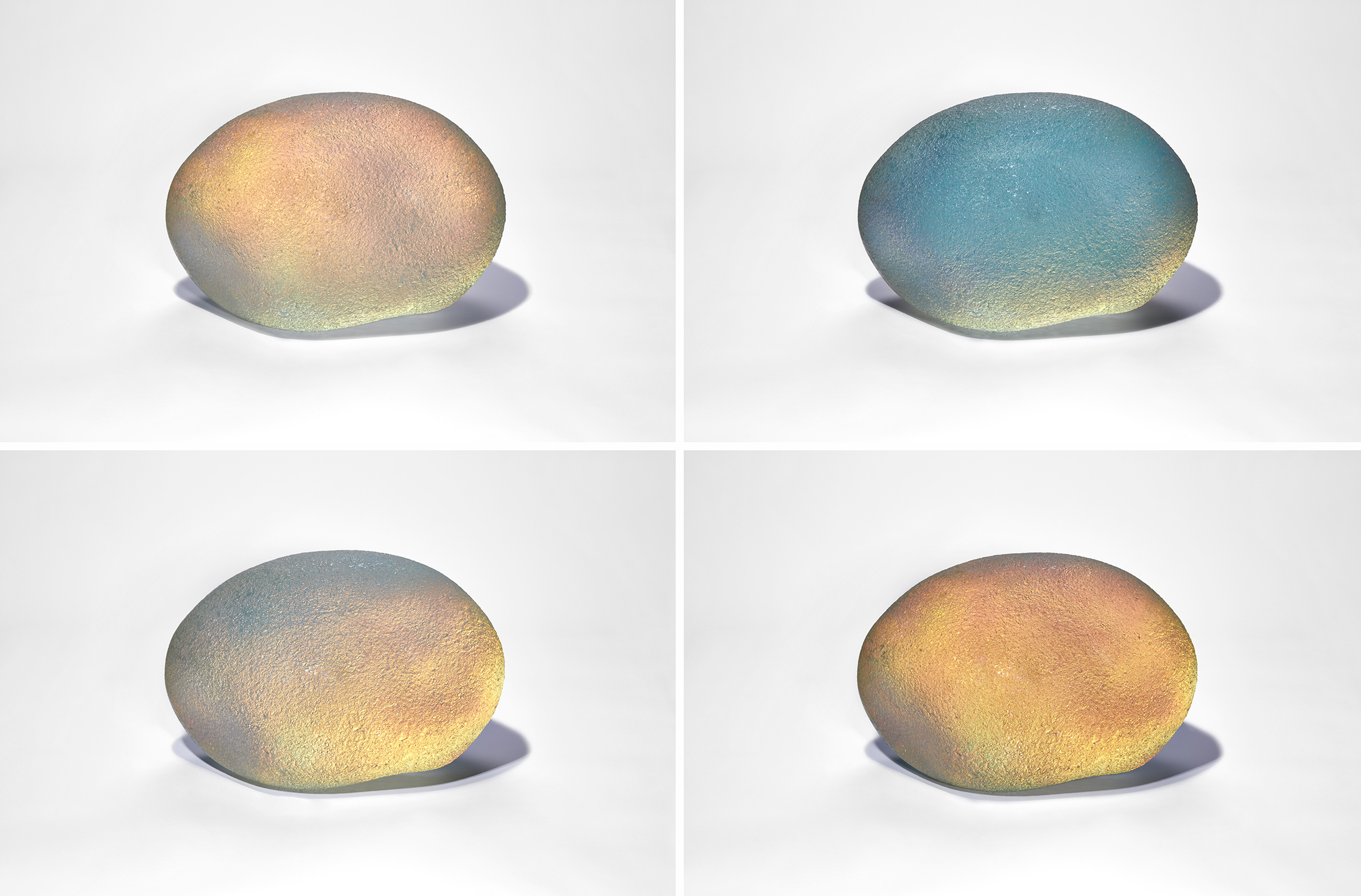

![]()

Ruby 2021, from the artist’s Meteorites series

After graduating, Lewis worked as a technician in the glass department at Stafford University. In 1994, an unexpected job offer led him to Oregon, where he spent seven months in the forests near Port Orford on the West Coast as assistant to the American glassmaker, James E. Nowak. It was here that he first experimented with glass coated in a dichroic filter. When Lewis returned from the US, he made stained glass windows to earn a living, while at the same time continuing to experiment with dichroic filters. In the 1990s, such filters were made of glass and extremely expensive. In 2000, however, a new plastic film with a dichroic filter of comparable quality but many times cheaper was brought onto the market. This was a vital development for Lewis, since it enabled him to use the filter much more widely in his work.

A dichroic filter only allows a particular frequency of light to pass through it. When it is inserted onto a piece of glass, then, depending on the angle at which the glass is viewed, the frequency and so the colour of the light will change, creating a shimmering effect. This works particularly well with a single light source, refracted through the glass to produce a very pure light that can be projected onto a background surface.

At first Lewis made cuboids containing trapped insects. A breakthrough moment came, however, when he inserted a dichroic filter into a glass sphere, and it started to glow. This led him to develop the Moon Rock, a type of sculpture which is made from two solid masses of glass joined along a flat surface that has been coated with a filter. The size, shape and texture of each ‘moon rock’ can vary, as can the composition of the filter, allowing different ‘rocks’ to glow different colours; Lewis’s own favourite is an eerie violet. The Moon Rock sculptures capture the softness of light and transform the hardness of glass into a different, softer material. Like naturally occurring moonstones, the Moon Rocks have an inner luminosity, although theirs is more highly coloured, almost fluorescent, like butterfly wings or something out of a science fiction movie. Lewis has also made scent bottles with dichroic filters on the dippers, enabling the light to be projected down into the bottles and create an interior glow.

The ‘moon-rock’ design has been licensed for several architectural commissions, including at hotels and hospitals. The most important to date is the Bleigiessen sculpture, an installation by Thomas Heatherwick in the headquarters of the Wellcome Trust, London. This incorporates 150,000 clear spherical glass beads, made to Lewis’s design with a dichroic filter, which are suspended from wires and appear to cascade like a prismatic waterfall through a 30-metre high atrium.

In another commission, part of a design by Mallinson Architects for the Child Museum in Cairo, the ‘moon-rock’ design was incorporated into glass tiles that were used to cover the surface of 2.5 metre-high spheres. These were then affixed to the ‘Space Pyramidion’, a towering structure of coloured rods and hoops that represents planets in orbit. Lewis also designed an earthquake simulator for the museum, using a series of electric motors and transformers which he had to bring out on the plane from England.

Architectural commissions aside, he has developed a range of Moon Rock sculptures that are individual pieces of art, to be displayed either on their own or in clusters. Some have a smooth, sensual finish, like satin. Others, like Gold Moon Rock, are lightly or heavily textured by chipping away at their surface –– a process requiring hours of patient, careful labour with a metal centre-punch. He wants them to convey the sense of timelessness, “as if they were maybe from a different planet––they look like they have fallen out of the sky.” Distant Electric Vision, he says, “will feature the largest and purest Moon Rocks I have ever made.”

As part of his practice, Lewis also teaches glassblowing. While this was put on hold during the lockdown, he has since restarted his workshops at Parndon Mill. “I think people are just fascinated by glassblowing. Most of them say, ‘I’ve wanted to do it since I was a kid,’ and they love it.” This fascination is one which he shares. “Glass is just an amazing material, only very difficult. Everything is a challenge.”

In the future, he has ambitions to make work on a more monumental scale, and to find a way of combining the rusty aesthetic of the Apertura pieces with the luminosity of the Moon Rocks: “at some point they’ve got to have some kind of connection.” Ultimately, for him, the purpose of his art is self-expression. “I think that’s what everyone strives to do: to have their own voice.” This exhibition will enable viewers to experience Jon Lewis’s unique voice for themselves.

Further information;

- Distant Eletric Vision Artworks | Further artworks by Jon Lewis

- Frequent contributor Emma Park is a London-based arts writer and podcaster with a focus on the fine arts, classics, and education

- Photography by Agata Pec, Matthew Booth and Jon Lewis

![]()

The many colours emitted from the Gold Moon Rock 2021

![]()

The artist in action

![]()

Artist's sketchbook page

![]()

Recent photoshoot

![]()

Phateon and Icaron on display for the group exhibition CAD at the Argentine Ambassador's Official Residence

If an artist’s studio reflects his personality, then Jon Lewis might be an eccentric inventor as much as a glassblower. In his workshop in Parndon Mill, a community of makers in Harlow, Essex, the cupboard doors are papered with enigmatic lists and diagrams, while inside there are trays piled high with drills, diamond-tipped polishers and obscure parts of machines. Wicker baskets hang next to wire mesh on hooks jutting from the roof beams. Boxes of Kugler colours are stacked on top of an old chest. Between the windows, shelves nailed into the whitewashed brick wall display a cabinet of curiosities: glass vessels in various shapes and colours, a wooden letter ‘M’ wrapped in tinfoil, and a steel winch attached to a glass bulb. A cactus, a toy truck and a stained glass panel sit side by side on a windowsill. In a dark corner, a tall steel rod that has been hacked into by an angle grinder stands on its end like a worm-eaten apple core.

The artist’s studio

In the garden outside the studio is a large “automatic grinding machine”, as Lewis calls it, which he made himself from a marine winch gearbox and some pallet trunk rollers, and which he uses for polishing. One of his most striking characteristics as a glassmaker is just this element of resourcefulness: he has adapted or made much of his own equipment, including even a glory hole and a furnace, in the service of his distinctive aesthetic. This aesthetic, combining the machine & hand-made, cold metal and warm glass, takes centre stage at his first solo exhibition with Vessel Gallery.

Lewis’s most ambitious collection to date is Apertura, a series of glass sculptures, coated in iron ore, in the shape of tall standing stones; he called the earliest Monoliths. In each sculpture, two panels of glass on opposite sides, usually oblongs, have been left free of iron: these are the ‘apertures’, reminiscent of windows or screens. One of the works in this series, Apertura Aurora, won the Glass Society Award at the British Glass Biennale 2019. It contains two large panes of thick transparent glass, half-stained with purple, which encourage the viewer to look at or through them, into the sculpture and out the other side at a world distorted by the double refraction of light. The purple of the apertures is complemented and enhanced by the reddish rust of the iron coating.

“These vessels try to capture and frame a small plane of glass and colour,” says Lewis. “Sometimes, a small rectangle of handmade glass is just beautiful on its own.” The individual appeal of the glass is enhanced by the variation & graduation in the colours with which each piece is stained. Lewis even deliberately leaves a few bubbles in order to echo the texture of medieval glass. This detail goes back to the first five years of his career, when he made stained glass windows.

The glass in the Apertura series is made from the screen fronts of Bang & Olufsen Beovision 1 television sets that were, according to Lewis, top-of-the range when they came out in the early 2000s. These are made of a grey, very lead-rich glass with a high refractive index that makes it sparkle. At the same time, this type of glass was made to be pressed into a mould, so it is viscous and resistant to blowing.

To make an Apertura sculpture, Lewis first melts the television glass and blows it into the desired shape. He then applies an angle grinder to an iron core to generate a continuous shower of sparks whose heat allows them to be impregnated into the surface of the glass. He realised that iron sparks could be used in this way from a chance discussion with a friend, who described how he had accidentally fused iron onto a window he was installing. The iron that Lewis uses is all scrap metal, including metal frames from the salvaged televisions. The process, he says, feels rather “industrial”: he has to don a mask, earphones, a hat and leather jacket. “The whole place gets covered in metal.” The iron layer is substantial enough that magnets will stick to it – not something you would expect of glass.

Showering an artwork with iron, a process the artist called ‘spark impregnation’

Once the glass is coated with iron, except for the two ‘apertures’, he further patinates it by applying home-made ‘rubs’ of wine and chilli sauce, salt and coffee grains. He then leaves the sculpture outside where it will be exposed to the elements and where the ‘rub’ will speed up the process of patination. This stage could take anything from a couple of hours to years, depending on the depth and colouring of the texture that he wants to achieve. At the end, he will seal the patina with a layer of matt varnish to preserve it.

Transceiver, 2021

Another work from the Apertura series, Transceiver, refers more explicitly to the idea of the television. Transceiver consists of two ovoid glass sculptures, one taller and rustier, one shorter and more ashen in colour, extending upwards into tapering cones reminiscent of aerials. The plinths on which they stand are hollowed out, so as to suggest a sort of channel between them. It is as though they were transmitting ethereal messages above and below ground, to be displayed on the long, thin screens of graduated purple glass fading to yellow, while the screens themselves seem to turn away from each other, like two strange beings trapped inside the hard, impersonal casing and unable to communicate directly. In the twenty-first century, says Lewis, “we seem to look at life through a screen.” The pair of sculptures conjure up a sense of claustrophobia and isolation.

Transceiver received an honourable mention in the Glass Art Society’s 2021 exhibition Trace, which highlighted works that explored ideas of sustainability & ‘green’ glassmaking. Lewis, who was born in 1967, derives his artistic use of recycled materials from his childhood in the Malvern Hills, when he used to dig up pieces of Victorian glass and pottery from a bottle tip on a nearby farm. “That’s all that’s left from the Victorian age…glass and ceramics survive where nothing else would.” For similar reasons, glass is an ideal material not only for recycling, but for art about recycling; more clearly than most media, it embodies the process of taking one form and changing it into another. “I’d been recycling glass bottles and all sorts of things over the years,” he says. The idea of using television glass specifically came to him after a project with a friend where they used waste glass from a company that recycled televisions, which had turned a “weird, stony green colour”, to make stained glass windows.

‘Distant Electric Vision’, the title of the exhibition, is a phrase that was first used in 1908 by the engineer A.A.Campbell Swinton, who presciently described the principles of the television years before the technology existed to make one. The title alludes to the fusion of prehistoric and futuristic themes in works like the Apertura series, with their enclosure of modern TV glass within primitive iron ore.

The reference to Campbell Swinton also goes back to Lewis’s early training in electronics and computing, which he began after he left school at sixteen. At eighteen, however, he contracted glandular fever, and was out of action for six months. It was this illness which led to his decision to change direction and enrol at Hereford Art College for a year. Still unsure what to specialise in, he was leafing through a copy of his mother’s Lady magazine in an idle moment when he came across a feature about a glassblower who made perfume bottles. He was fascinated, and immediately applied to Wolverhampton University to do a BA in glass. This took him four years, from 1989-1993, including a year’s practical training at the former International Glass Centre at Brierley Hill, Stourbridge. At Wolverhampton, he made coldworked glass arrowheads, inspired by prehistoric flint tools; this was an early foray into the theme of glass as something ancient that can be found in the earth. This theme is continued in another series, Meteorites, which balances rusty surfaces with spirals of colour, juxtaposing what he calls ‘machine life’ with the suggestion of organic matter and DNA.

Ruby 2021, from the artist’s Meteorites series

After graduating, Lewis worked as a technician in the glass department at Stafford University. In 1994, an unexpected job offer led him to Oregon, where he spent seven months in the forests near Port Orford on the West Coast as assistant to the American glassmaker, James E. Nowak. It was here that he first experimented with glass coated in a dichroic filter. When Lewis returned from the US, he made stained glass windows to earn a living, while at the same time continuing to experiment with dichroic filters. In the 1990s, such filters were made of glass and extremely expensive. In 2000, however, a new plastic film with a dichroic filter of comparable quality but many times cheaper was brought onto the market. This was a vital development for Lewis, since it enabled him to use the filter much more widely in his work.

A dichroic filter only allows a particular frequency of light to pass through it. When it is inserted onto a piece of glass, then, depending on the angle at which the glass is viewed, the frequency and so the colour of the light will change, creating a shimmering effect. This works particularly well with a single light source, refracted through the glass to produce a very pure light that can be projected onto a background surface.

At first Lewis made cuboids containing trapped insects. A breakthrough moment came, however, when he inserted a dichroic filter into a glass sphere, and it started to glow. This led him to develop the Moon Rock, a type of sculpture which is made from two solid masses of glass joined along a flat surface that has been coated with a filter. The size, shape and texture of each ‘moon rock’ can vary, as can the composition of the filter, allowing different ‘rocks’ to glow different colours; Lewis’s own favourite is an eerie violet. The Moon Rock sculptures capture the softness of light and transform the hardness of glass into a different, softer material. Like naturally occurring moonstones, the Moon Rocks have an inner luminosity, although theirs is more highly coloured, almost fluorescent, like butterfly wings or something out of a science fiction movie. Lewis has also made scent bottles with dichroic filters on the dippers, enabling the light to be projected down into the bottles and create an interior glow.

The ‘moon-rock’ design has been licensed for several architectural commissions, including at hotels and hospitals. The most important to date is the Bleigiessen sculpture, an installation by Thomas Heatherwick in the headquarters of the Wellcome Trust, London. This incorporates 150,000 clear spherical glass beads, made to Lewis’s design with a dichroic filter, which are suspended from wires and appear to cascade like a prismatic waterfall through a 30-metre high atrium.

In another commission, part of a design by Mallinson Architects for the Child Museum in Cairo, the ‘moon-rock’ design was incorporated into glass tiles that were used to cover the surface of 2.5 metre-high spheres. These were then affixed to the ‘Space Pyramidion’, a towering structure of coloured rods and hoops that represents planets in orbit. Lewis also designed an earthquake simulator for the museum, using a series of electric motors and transformers which he had to bring out on the plane from England.

Architectural commissions aside, he has developed a range of Moon Rock sculptures that are individual pieces of art, to be displayed either on their own or in clusters. Some have a smooth, sensual finish, like satin. Others, like Gold Moon Rock, are lightly or heavily textured by chipping away at their surface –– a process requiring hours of patient, careful labour with a metal centre-punch. He wants them to convey the sense of timelessness, “as if they were maybe from a different planet––they look like they have fallen out of the sky.” Distant Electric Vision, he says, “will feature the largest and purest Moon Rocks I have ever made.”

As part of his practice, Lewis also teaches glassblowing. While this was put on hold during the lockdown, he has since restarted his workshops at Parndon Mill. “I think people are just fascinated by glassblowing. Most of them say, ‘I’ve wanted to do it since I was a kid,’ and they love it.” This fascination is one which he shares. “Glass is just an amazing material, only very difficult. Everything is a challenge.”

In the future, he has ambitions to make work on a more monumental scale, and to find a way of combining the rusty aesthetic of the Apertura pieces with the luminosity of the Moon Rocks: “at some point they’ve got to have some kind of connection.” Ultimately, for him, the purpose of his art is self-expression. “I think that’s what everyone strives to do: to have their own voice.” This exhibition will enable viewers to experience Jon Lewis’s unique voice for themselves.

Further information;

- Distant Eletric Vision Artworks | Further artworks by Jon Lewis

- Frequent contributor Emma Park is a London-based arts writer and podcaster with a focus on the fine arts, classics, and education

- Photography by Agata Pec, Matthew Booth and Jon Lewis

The many colours emitted from the Gold Moon Rock 2021

The artist in action

Artist's sketchbook page

Recent photoshoot

Phateon and Icaron on display for the group exhibition CAD at the Argentine Ambassador's Official Residence