Remnants | The work of Nicholas Arroyave-Portela by Dr Emma Park

25th November 2024

The work of Nicholas Arroyave-Portela by Dr Emma Park

For Nicholas Arroyave-Portela, ceramics might not have seemed like the most obvious career choice. He is descended from ‘a long line of doctors’: his father, a psychiatrist and son of a Colombian doctor and Spanish mother, was born in Cadiz, grew up partly in Colombia, and studied medicine at the University of Salamanca, Spain. He eventually migrated to Oxford to work for the NHS, and built up a private practice in London. His wife, also from Colombia, looked after their three children: two daughters and Nicholas (b. 1972), the youngest. Nicholas first came into contact with ceramics at the age of five. ‘I remember being in a class and the teacher gave us all a little ball of clay and taught us how to make a thumb pot,’ he says. ‘I was hooked from that moment onwards… I always intended to make it my life’s work.’

The artist throwing at the wheel. Photo © Michele Morea

When he was fourteen, his father died. In the transition from childhood to adulthood, he says, ‘it was a pivotal moment – bereavement made me grow up very quickly.’ Although his father was frequently away on business, Nicholas’s memory is of ‘a very loving man, very interesting… I think of the conversations I could have had with him.’

This relationship was the inspiration behind Todo sobre mi padre (‘Everything About My Father’), Arroyave-Portela’s 2010 exhibition, which he describes as ‘a reflection on his identity, my identity, and his migrant story.’ He feels a certain tension between being an ‘outsider’ on the one hand, and having a ‘sense of belonging’ to both English, Colombian and Spanish cultures: ‘I suppose they’re all part of me.’ The exhibition involved large-scale wall pieces, almost like ‘earthworks’, that were based on maps and flags and made using ‘deconstructed’ fragments of thrown pots built up in layers. A common preconception with ceramics is that they are just ‘objects’ to be read from an aesthetic point of view. But the works in this exhibition were ‘emotive’, he says: ‘I really put my feelings on the line, which was a very vulnerable place to be.’

Creating ‘deconstructed’ fragments from thrown pots. Photo © Michele Morea

In 1991, Arroyave-Portela entered the Bath College of Higher Education to study Three-Dimensional Ceramics. Upon graduating in 1994, he participated in a show at the Business Design Centre in London, and shortly after relocated to the city, renting a space in the studios of the British ceramist Kate Malone. ‘It was good to be in that environment,’ he remembers. ‘Kate had an amazing professional outlook and was already very successful by that point.’ In 1996, he was awarded a setting-up grant from the Crafts Council, which helped with living expenses and enabled him to purchase equipment such as a potter’s wheel and a sprayback wet booth, among other things.

He began to build up his practice, attending crafts fairs and obtaining gallery representation with Beaux Arts Bath and Adrian Sassoon, London. This enabled him, in 2000, to club together with a group of other artists to buy their own studio spaces in Broadway Market, east London. ‘I was a bit of a pioneer – when I moved in, there were still burning cars and the like,’ he remembers. ‘But a lot of artists were already working there… It was very affordable.’ Milestones in this period included a solo touring exhibition with the City Art Gallery, Leicester, and a residency in the Clay Studio, a ceramics centre in Philadelphia. It was here that he first became known to the American market, securing representation with the art historian and gallerist Helen Drutt English, and meeting influential collectors such as Marc Grainer. Today, he estimates that about 80 per cent of his work is bought by American collectors.

Another important step came in 2012, when he was commissioned by the Craft Study Centre to make ‘Consciousness’: A Personal Interpretation of The Mayan Long Count Calendar. This was a large-scale installation containing 260 thrown vessels that invoked the patterns of the Fibonacci Sequence and of a Mayan calendar that marked the time over just 5125 solar years, ending in 2012. Through this, he reflected on the idea of the cycles and rhythms of nature, through which indigenous peoples such as the Amerindians have integrated their spiritual and physical lives.

Consciousness | 2012 | Unique installation | H 300 cm W 320 cm D 40 cm. Photo © Nicholas Arroyave-Portela

In 2013, Arroyave-Portela relocated to Barcelona, which for him represented a ‘work-life balance’ that he had not found in London. ‘In Spain I am more conscious of the need to live in the present and enjoy the journey, as opposed to always trying to get to the destination.’ He has lived in Barcelona ever since, although he still keeps his studio in London. His identity is still very much a combination of cultures.

One major influence on Arroyave-Portela’s work is Abstract Expressionism. When he was in America, he enjoying looking at the big canvases of the Abstract Expressionists on display in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. For him, such works embody ‘the purest form of that expression – the painting and the gesture, the physicality’. The idea of the gesture, the expression of emotions through the hands, is also central to his own work. In this respect, clay is ‘an obvious means of recording expression.’ In recent years he has worked on developing an intuitive approach to making that connects his head, heart and hands.

At an early state, he was also influenced by the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu, who wrote cryptically that ‘the water that flows into the earthenware vessel takes on its form.’ He experimented with finding the shape of water, for instance by pouring it into plastic bags. He was also attracted by the idea of dehydration, and ‘the tautness and the crumpledness’ found in dehydrated fruit. He still recalls Philip Larkin’s poem Skin, which likens the ageing of Larkin’s own skin to the sagging, loosening and sand-blasting of an ‘old bag’.

For Arroyave-Portela, the process is as important as the finished piece; or to put it another way, the piece should be seen as a product, an expression of the process. He finds working with clay almost hypnotic, like a form of therapy. ‘Even if I wasn’t making things to sell, I would always need to be making,’ he says. Rather than approaching the material with a complete idea worked out in advance, he prefers to allow his hands to guide the material into shape. ‘For me it’s about letting go, letting the subconscious come through, freeing your physicality and just working with instinct. It’s as though your hands have their own mind. You’re not giving them instructions. It’s a very organic way of working.’

The present exhibition, Remnants, embodies a further development of Arroyave-Portela’s intuitive approach and his tactile intelligence. It includes work from two new collections: one of wheel-thrown vessels, and the other of three hanging sculptures. All the artworks are made of stoneware, which is his preferred material these days. ‘Stoneware has more of a solid feel to it,’ he says. ‘It has more longevity and more gravitas. It is very much an aesthetic decision.’ For his three wall pieces, he has chosen to work in three simple but powerful glazes: black, gold and white. The white is ‘a really delicious, stone-like glaze, with a matte finish’, that produces ‘a rich white surface’ – and which contains lots of tones within itself.

Remnants Solo exhibition. Photo © Agata Pec

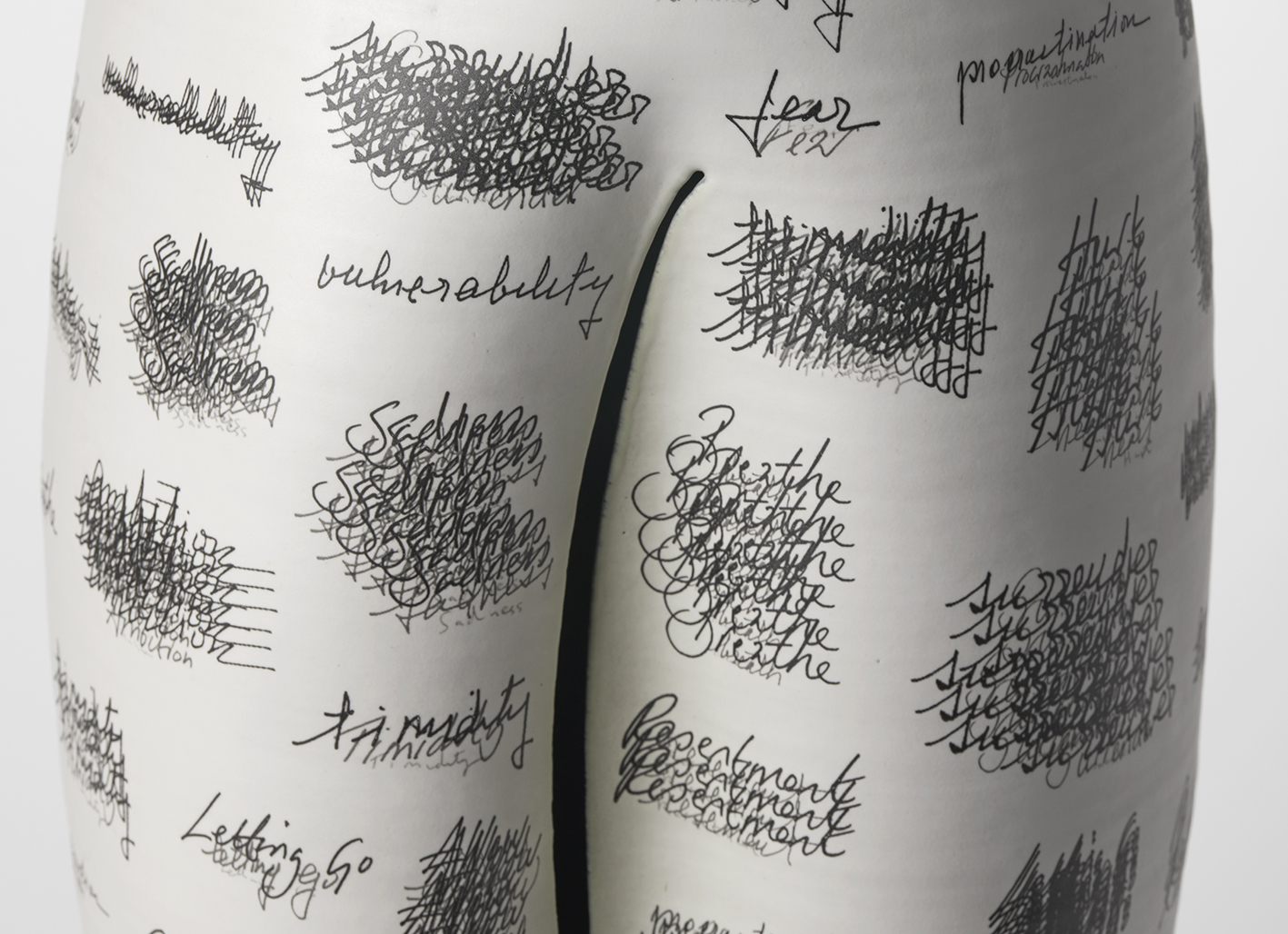

The latest series of vessels represent a return to simpler forms than his previous Crumpled series, and explore the vessel form as a medium of selfexpression. Over the top of the glazes, each in white or black, words from one of two lists have been transfer-printed in black or white respectively to provide a monochromatic contrast. The lists are entitled Looking Forward and Letting Go: they were both put together by the artist, his mother and his sister, who wrote out the words they associated with these ideas. Each word in the list was written out by hand by all three of them, and the sets of words in different hands were then layered one over the other with the aid of a graphic designer. ‘I wanted to get the essence of the words,’ Arroyave-Portela says, ‘almost like a vibration.’

Detail from Letting Go No 141. Photo © Agata Pec

His use of words was also inspired by a Japanese scientist, Dr Masaru Emoto, who has experimented with the different patterns formed by frozen water in apparent response to different human words.

The wall pieces, collectively entitled Lost Intentions, represent Arroyave-Portela’s desire to return to a format that he has previously used, but with a ‘new informed appreciation’ of it that allows him to move forward ‘with a different consciousness’. He draws inspiration from several contemporary artists in different media, including the Spanish painter, sculptor and ceramist Miguel Barcelo, whose ‘gestural, brutish’ forms Arroyave-Portela admires. ‘What he does on a large scale is incredible,’ he says. He is also influenced by the Catalan ceramic artist Claudi Casanovas, who treats clay as ‘geology…. He’s thinking about how to construct something like earthworks – things that happen in natural phenomena, like the way the lava flows in volcanoes or the way cracks build up through pressure.’

Arroyave-Portela’s own wall pieces represent a further development of his exploration of ‘touch-based emotion’. ‘There’s something in them that expresses itself without me having to go into detail,’ he says. While he may have ideas or images in mind while making them, ultimately, what matters is the way their thick, cracked surfaces speak directly to the viewer’s heart, without the need for words.

Lost Intentions in Black No 138. Photo © Agata Pec

Remnants A solo exhibition 6 November - 18 December 2024

Further works by the artist

Arroyave-Portela's creations are all thrown on the wheel using his own unique technique. Pulling up as much clay from the bottom mass as possible, the clay walls of each piece are created thin and even, maximising the artist’s ability to manipulate the form while the material is still soft and malleable.

Additional porcelain slips are sometimes applied to create further surface textures and layering. After the first initial bisque firing (1080 degrees) glazes are applied by using various methods such as spraying and pouring, a process often repeated several times after each firing of 1260 degrees. The multi-firing process allows for the build-up of the glaze, creating a rich palette of tones and finishes.

Remnants Solo exhibition. Photo © Agata Pec

Arroyave-Portela’s works can be found in various major museums and private collections worldwide including: 'Home, Hogar' Arts Two building, Queen Mary, University of London (UK), The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (UK), Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (UK), The National Museums and Galleries, Liverpool (UK), Leeds City Gallery, Leeds (UK), The Contemporary Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii (USA), The Philadelphia Museum of Art (USA), Houston Centre for Contemporary Art (USA), The Mint Museum (USA).

Nicholas Arroyave-Portela. Photo © Michele Morea