Donald Baugh by Dr Emma Park

16th October 2024

Donald Baugh by Dr Emma Park

In art, there are different kinds of originality. For Donald Baugh, being a designer and woodworker is not about ‘inventing’ something that no one else has ever come up with before, like a scientist. Rather, it is about authenticity: about making what he wants to make. ‘You can’t copy somebody’s aesthetics,’ he says. ‘If you do, you’ll always be behind them. You have to find your own aesthetics. It’s your fingerprint.’ In fact, Baugh’s vessels and abstract sculptures feel very distinctive. This should come as no surprise, because they are the culmination of decades of experience in woodworking, design, personal experience, and observation of the world.

Baugh’s parents emigrated to the UK from Jamaica in the 1950s. ‘They were the Windrush generation,’ he says. They first settled in Chiswick, where he was born in 1961. However, Baugh’s mother took him and his two sisters back to Jamaica from the ages of one to eight, where he lived with his grandparents while his parents established themselves in London. ‘It was quite normal at the time,’ he recalls. When he returned to London, ‘it was horrible – the weather, and the lack of freedom.’ His mother was a nurse and his father worked as a machine operator at Nestlé. ‘It was quite a strict upbringing, but when I was an adult, I appreciated it.’

At his all-boys’ comprehensive school, Baugh excelled in running and was ranked in the top 50 in the country for the 800 metres. As athletes, he remembers, ‘we realised the power we had, because we could improve the school’s reputation. People always say, “What’s politics got to do with sport?” And I say, “Everything.”’ He has continued running regularly in his spare time since then. He still comes across as an athlete with a latent strength – a quality doubtless helpful for the sheer physical effort required in working a resistant material like wood.

Baugh left school at sixteen and took an apprenticeship at Vickers-Rolls Royce, where he spent three years making parts for machinery and learning metal-working skills such as welding. After the first year, he realised he did not enjoy working with metal as a material, so he started attending night school classes in carpentry and drawing. Thus, at the age of nineteen, he was able to start working as an assistant cabinet-maker. He continued in this profession into his twenties while at the same time taking vocational courses in interior design, upholstery and photography. When he needed extra money, he worked on building sites. In his spare time, he travelled around Europe, an experience which he remembers fondly: ‘I ended up talking to so many kinds of people.’

Baugh first discovered contemporary art in his early twenties, when one of his trips took him to Venice, leading to a chance encounter with the Biennale. ‘I was fascinated – how did they make that? They were like gods to me. I started buying the magazines.’ Back home, he had just started to work for a table-making company, when he injured his knee after a competition, and decided to give up competitive athletics.

It was at the age of 29 that he finally discovered his true vocation. He was awarded a government grant to study for three years at Rycotewood, a furniture-making college in Oxford, from which he graduated in 1996. ‘It was the best time in my life,’ he says. ‘We learnt everything about woodworking. The first semester, we weren’t even allowed to use any machinery.’ The course also taught him how to design furniture and to run his own business. He then spent two further years studying for a Higher National Diploma in three-dimensional furniture design at Middlesex University. This exposed him to other crafts, including ceramics, textiles and printing; he was particularly inspired by the forms he encountered in the ceramics department. He was also drawn to the aesthetic styles of Charles Eames and the Bauhaus. These influences are visible in the streamlined abstractions of pieces like Uhura 0.3, a 60-centimetre tall sculpture in dark-stained ash with a narrow vase-like base and mouth emerging at either end of an asymmetrical parallelogram body.

![]()

Donald Baugh | Photo © Violeta Sofia

Baugh spent the next few years working for a variety of furniture-makers. Then he had an accident, nearly sawing off his hand at the wrist. (Woodworking is a perilous craft: just before the pandemic, he almost severed two fingers.) This experience jolted him into deciding that it was time to practise on his own behalf, so he set up a furniture business at a studio space in Kew.

It was there that he met Karin-Beate Phillips, the director of British European Design Group, a company that specialised in exhibiting home-grown design abroad. She invited Baugh to exhibit his furniture at a show in New York in 2013. This was a breakthrough moment, marking the beginning of his career as an independent designer-maker. Since then, an increasing proportion of his time has been devoted to making his own designs and exhibiting them around the world. A trip to Tokyo for a show made him realise the value of making smaller-scale pieces that could easily be transported; since then, he has continued to explore at a more portable scale, as well as to continue working on bigger pieces.

Today, Baugh rents a workshop space from Tom Vaughan at Object Studio, in a unit on an industrial estate in Walthamstow, east London. As part of his practice, he also makes bespoke furniture, kitchens and storage units. To find his workshop, where he has worked freelance for nearly a decade, you have to walk through a maze of warehouses with corrugated iron roofs and breeze blocks containing everything from packaged fast food to stone table-tops. The two storeys of the unit shared by Object Design, Bode Design and CNC Projects are filled with sacks of wood shavings and large-scale equipment. The air is dusty and conversation is frequently interrupted by the rasp of sawing or the buzz of the CNC machine, which, when I visited, was carving a design into a huge piece of raw pink plastic foam at the back of the building.

Baugh’s own workshop, half way along the ground floor, is a windowless space piled high with planks, blocks of wood and boxes of tools. Before picking up his tools, however, he usually starts by exploring a new idea in a sketchbook at his home in Ealing. Coming late to computerised design, he still prefers working by hand where possible. ‘I’ve always had a sketchbook,’ he says. ‘When I started out as a designer, I was like a sponge, taking everything in. Wherever I went, I was looking at things and trying to work out how they were made.’

![]()

The artist's hands © Alun Callender

At the workshop, he showed me a collection of large cardboard silhouettes, cross-sections representing the approximate shape of his vases. Being drawn by hand, they are free form, and deliberately asymmetrical. He also makes prototypes in 3D-printed plastic, some of which adorn the shelves in his corner of the shared office upstairs. Some of the prototypes are reminiscent of shells with highly sculpted curves. Their bulging, organic shapes are reflected at a larger scale in several of his finished sculptures, each with their own variations, such as Lun Green, which has an acrylic sprayed mouth and a black finish, and Bulla, in which the ash is given a different sheen and texture through staining and oiling. ‘I’m a bit of a beachcomber,’ he says. ‘When I’m on holiday, I’ll collect little pebbles and driftwood that has been moulded by the sand and the water.’ A piece of dried wood that he found in Richmond Park sits on his shelf. ‘I’d like to make a sculpture mimicking its form one day.’ When he is out for a walk, he takes photographs of textures and patterns that interest him.

The laborious process from blocks of wood to a finished vase can take three or four months. For editions of several pieces he might enlist the help of a CNC machine to carve the wood according to a digitally designed image, but for unique pieces he will always work by hand. He speaks about a close connection with the wood. When we were talking in the office, he picked up a block of ash and ran his fingers along it. ‘Sometimes when you pick a piece of wood up, you can just feel it in your fingertips… I don’t know what you can feel, exactly. It’s an energy, an excitement.’ The connections between humankind and wood, he points out, go back a very long way: it is one of the very oldest raw materials. For him, wood is ‘almost like a nervous system.’

He enjoys working with bright, saturated colours of acrylic, which he spray-paints onto sections of his wooden sculptures in thick layers. The smooth, glowing surface provides a striking contrast with the darker grain of the wood with its intricate patterns. The ‘vibrancy’, he says, also takes him back to his childhood in the Caribbean. ‘The land is so fertile there – things just grow.’ Sitting on his desk is an early free-form sculpture in tulip wood, lightly sandblasted and partly sprayed in pale pink, which represents an abstract version of a sewing machine, in tribute to T. Michael, a Norwegian friend who is a fashion designer.

Baugh smiles mischievously as he recounts how he met Angel Monzon, creative director of Vessel Gallery, for the first time. A few years ago, he happened to be in Notting Hill, walking past the gallery, when he made the decision to go inside and talk to Monzon. At the time, only one wooden object was on display. ‘It was the first time I had walked into a gallery and enquired about the possibility of doing a show,’ Baugh recalls. ‘Angel was helpful and gave me good advice. Part of me thought that we would end up doing a show together one day.’ This year’s Collect featured an unusually large number of wooden sculptures. Not long after the fair, Baugh received an invitation from Monzon to send him some work – and the rest is history.

When I ask Baugh if wood is ‘having a moment’, he argues that it is more than that. ‘I think it’s here to stay,’ he says. ‘I think more people will turn to it. It’s the most natural material. Everyone relates to it.’

![]()

The artist at work | Photo © Alun Callender

The present exhibition intentionally coincides with Black History Month. It shows a collection of vessel-like sculptures based on Baugh’s reflections during the pandemic, although the first such vessel he made was finished just before the first lockdown. One of the most striking pieces from this collection is Zurri 0.1, a sand-blasted vase in tulip wood with an exaggerated curling lip that has been spray-painted bright orange, while the side of the vase has been carved with runic designs reminiscent of the traditional facial markings found in parts of sub-Saharan Africa. This sculpture is conceived as part of a collection of three vessel-shaped Zurri sculptures that will reflect on Baugh’s ancestry, which ultimately runs through the Caribbean back to Africa, and which he hopes to trace more precisely through a DNA test. As he puts it, ‘my Union Jack is one in the colours of Jamaica.’ In making Zurri, he began to realise that ‘indigenous people from around the world used the same tools, and you see a repetition of patterns’. He plans to explore this idea further elsewhere in the collection.

Also on display are three sculptures from his Masai series: long wooden statues suggesting human figures in the abstract. These sculptures represent a creative response to a myth told by the Kenyan tribe that their ancestors were once upon a time visited by giants with enormous heads; they also recall the colossal heads of the Olmec civilisation discovered in Mexico. Baugh’s eventual aim is to make a substantial collection of them to put in an installation. ‘They’re getting taller and taller,’ he says. In the future he also plans to make a more ‘figurative’ collection based on the female form.

In 2024, Baugh’s career as a sculptor in wood is well on its way: he already has several exhibitions in the pipeline for the coming year, including one in Venice. He is also planning to do a show with glass and metal artist Chris Day (also represented by Vessel), of Jamaican descent on his father’s side, and ceramist Chris Bramble, whose work draws on Zimbabwean traditions. Baugh’s interest in his heritage can be seen in The Chair of Uncomfortable Truths (2023), which reflects on the slave trade, including the major role played in it by religion. The ‘Chair’ is designed for two people to sit together back-to-back. If you do this with a stranger, Baugh says, ‘there’s an element of uncomfortableness’. Its design, complete with nails, chains and crossbar, evokes a crucifixion, and also reflects on the way in which slaves in the marketplace were treated as mere chattels. It is accompanied by a commemorative poem by the writer Komali Scott-Jones.

Baugh describes himself as ‘a dreamer’ who is always thinking up new ideas. ‘If I won the lottery,’ he says, ‘I would invest it in the best workshop and facilities, and in travelling to learn about other crafts.’ He hopes one day to make a sculpture in which an external form is repeated within the interior, ‘like a Russian doll’, and to develop a technique for sandblasting, ‘so that the wood is nearly transparent and you can see its veins.’ Wherever he goes next, the imaginative and beautifully executed works he has produced so far demonstrate the true originality of Donald Baugh as an artist, and the strength of wood as a medium for sculpture.

AKANSA solo exhibition 1 - 31 October 2024

Further Works by the artist

![]()

Uhuru 0.3

Unique | Ash | H 60 cm W 35 cm D 9 cm

Photo © Agata Pec

![]()

Umama 0.1

Unique | Ash | H 151 cm W 47 cm D 27 cm

Photo © Violeta Sofia

![]()

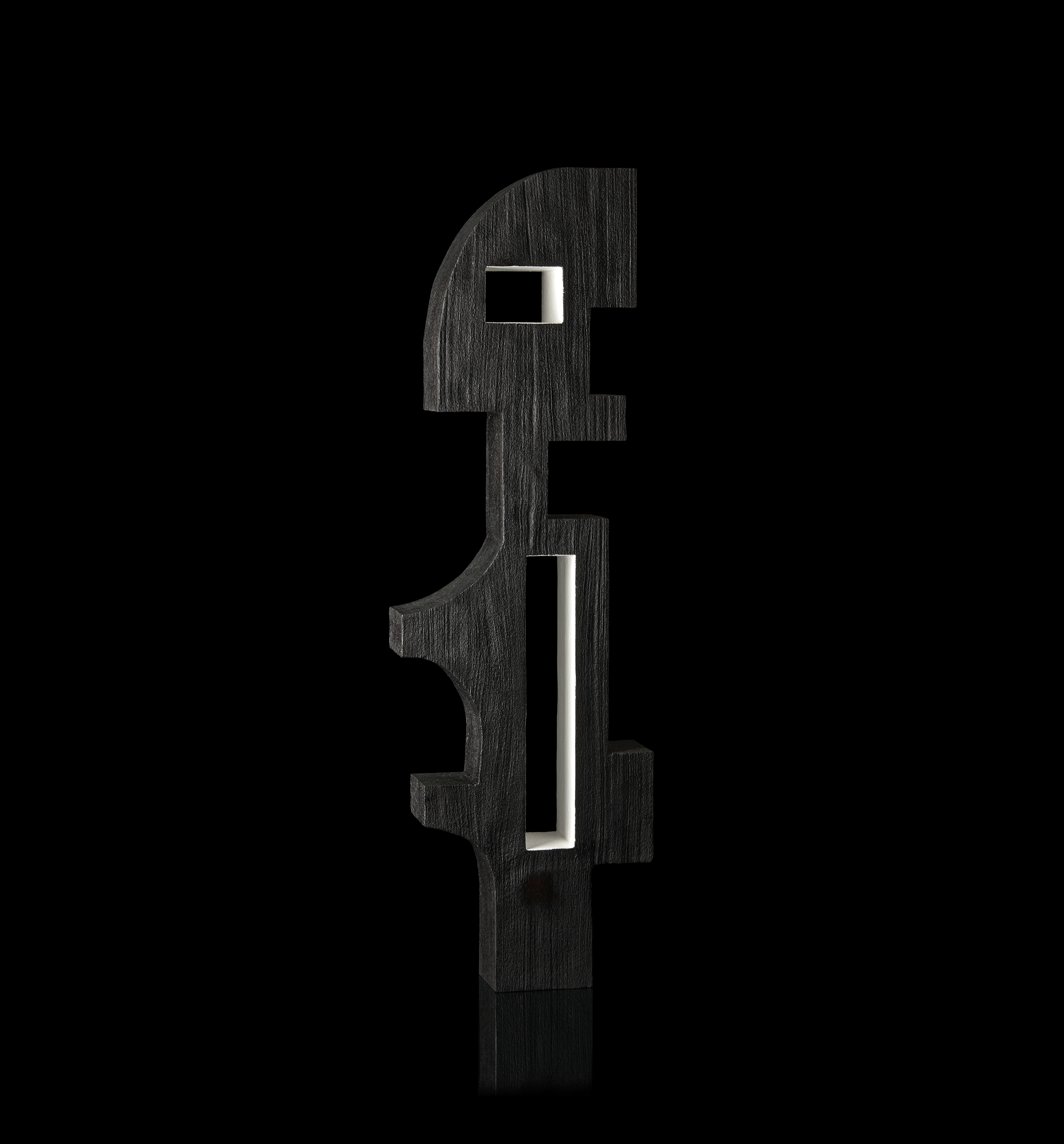

Masai 0.1

Unique | Sapele | H 89 cm W 28 cm D 9cm

Photo © Agata Pec

![]()

Zurri 0.1

Unique | Tulip Wood | H 56 cm W 35 cm D 17 cm

Photo © Violeta Sofia

![]()

Kakra 0.2

Unique | Tulip Wood | H 48 cm W 23 cm D 13 cm

Photo © Agata Pec

In art, there are different kinds of originality. For Donald Baugh, being a designer and woodworker is not about ‘inventing’ something that no one else has ever come up with before, like a scientist. Rather, it is about authenticity: about making what he wants to make. ‘You can’t copy somebody’s aesthetics,’ he says. ‘If you do, you’ll always be behind them. You have to find your own aesthetics. It’s your fingerprint.’ In fact, Baugh’s vessels and abstract sculptures feel very distinctive. This should come as no surprise, because they are the culmination of decades of experience in woodworking, design, personal experience, and observation of the world.

Baugh’s parents emigrated to the UK from Jamaica in the 1950s. ‘They were the Windrush generation,’ he says. They first settled in Chiswick, where he was born in 1961. However, Baugh’s mother took him and his two sisters back to Jamaica from the ages of one to eight, where he lived with his grandparents while his parents established themselves in London. ‘It was quite normal at the time,’ he recalls. When he returned to London, ‘it was horrible – the weather, and the lack of freedom.’ His mother was a nurse and his father worked as a machine operator at Nestlé. ‘It was quite a strict upbringing, but when I was an adult, I appreciated it.’

At his all-boys’ comprehensive school, Baugh excelled in running and was ranked in the top 50 in the country for the 800 metres. As athletes, he remembers, ‘we realised the power we had, because we could improve the school’s reputation. People always say, “What’s politics got to do with sport?” And I say, “Everything.”’ He has continued running regularly in his spare time since then. He still comes across as an athlete with a latent strength – a quality doubtless helpful for the sheer physical effort required in working a resistant material like wood.

Baugh left school at sixteen and took an apprenticeship at Vickers-Rolls Royce, where he spent three years making parts for machinery and learning metal-working skills such as welding. After the first year, he realised he did not enjoy working with metal as a material, so he started attending night school classes in carpentry and drawing. Thus, at the age of nineteen, he was able to start working as an assistant cabinet-maker. He continued in this profession into his twenties while at the same time taking vocational courses in interior design, upholstery and photography. When he needed extra money, he worked on building sites. In his spare time, he travelled around Europe, an experience which he remembers fondly: ‘I ended up talking to so many kinds of people.’

Baugh first discovered contemporary art in his early twenties, when one of his trips took him to Venice, leading to a chance encounter with the Biennale. ‘I was fascinated – how did they make that? They were like gods to me. I started buying the magazines.’ Back home, he had just started to work for a table-making company, when he injured his knee after a competition, and decided to give up competitive athletics.

It was at the age of 29 that he finally discovered his true vocation. He was awarded a government grant to study for three years at Rycotewood, a furniture-making college in Oxford, from which he graduated in 1996. ‘It was the best time in my life,’ he says. ‘We learnt everything about woodworking. The first semester, we weren’t even allowed to use any machinery.’ The course also taught him how to design furniture and to run his own business. He then spent two further years studying for a Higher National Diploma in three-dimensional furniture design at Middlesex University. This exposed him to other crafts, including ceramics, textiles and printing; he was particularly inspired by the forms he encountered in the ceramics department. He was also drawn to the aesthetic styles of Charles Eames and the Bauhaus. These influences are visible in the streamlined abstractions of pieces like Uhura 0.3, a 60-centimetre tall sculpture in dark-stained ash with a narrow vase-like base and mouth emerging at either end of an asymmetrical parallelogram body.

Donald Baugh | Photo © Violeta Sofia

Baugh spent the next few years working for a variety of furniture-makers. Then he had an accident, nearly sawing off his hand at the wrist. (Woodworking is a perilous craft: just before the pandemic, he almost severed two fingers.) This experience jolted him into deciding that it was time to practise on his own behalf, so he set up a furniture business at a studio space in Kew.

It was there that he met Karin-Beate Phillips, the director of British European Design Group, a company that specialised in exhibiting home-grown design abroad. She invited Baugh to exhibit his furniture at a show in New York in 2013. This was a breakthrough moment, marking the beginning of his career as an independent designer-maker. Since then, an increasing proportion of his time has been devoted to making his own designs and exhibiting them around the world. A trip to Tokyo for a show made him realise the value of making smaller-scale pieces that could easily be transported; since then, he has continued to explore at a more portable scale, as well as to continue working on bigger pieces.

Today, Baugh rents a workshop space from Tom Vaughan at Object Studio, in a unit on an industrial estate in Walthamstow, east London. As part of his practice, he also makes bespoke furniture, kitchens and storage units. To find his workshop, where he has worked freelance for nearly a decade, you have to walk through a maze of warehouses with corrugated iron roofs and breeze blocks containing everything from packaged fast food to stone table-tops. The two storeys of the unit shared by Object Design, Bode Design and CNC Projects are filled with sacks of wood shavings and large-scale equipment. The air is dusty and conversation is frequently interrupted by the rasp of sawing or the buzz of the CNC machine, which, when I visited, was carving a design into a huge piece of raw pink plastic foam at the back of the building.

Baugh’s own workshop, half way along the ground floor, is a windowless space piled high with planks, blocks of wood and boxes of tools. Before picking up his tools, however, he usually starts by exploring a new idea in a sketchbook at his home in Ealing. Coming late to computerised design, he still prefers working by hand where possible. ‘I’ve always had a sketchbook,’ he says. ‘When I started out as a designer, I was like a sponge, taking everything in. Wherever I went, I was looking at things and trying to work out how they were made.’

The artist's hands © Alun Callender

At the workshop, he showed me a collection of large cardboard silhouettes, cross-sections representing the approximate shape of his vases. Being drawn by hand, they are free form, and deliberately asymmetrical. He also makes prototypes in 3D-printed plastic, some of which adorn the shelves in his corner of the shared office upstairs. Some of the prototypes are reminiscent of shells with highly sculpted curves. Their bulging, organic shapes are reflected at a larger scale in several of his finished sculptures, each with their own variations, such as Lun Green, which has an acrylic sprayed mouth and a black finish, and Bulla, in which the ash is given a different sheen and texture through staining and oiling. ‘I’m a bit of a beachcomber,’ he says. ‘When I’m on holiday, I’ll collect little pebbles and driftwood that has been moulded by the sand and the water.’ A piece of dried wood that he found in Richmond Park sits on his shelf. ‘I’d like to make a sculpture mimicking its form one day.’ When he is out for a walk, he takes photographs of textures and patterns that interest him.

The laborious process from blocks of wood to a finished vase can take three or four months. For editions of several pieces he might enlist the help of a CNC machine to carve the wood according to a digitally designed image, but for unique pieces he will always work by hand. He speaks about a close connection with the wood. When we were talking in the office, he picked up a block of ash and ran his fingers along it. ‘Sometimes when you pick a piece of wood up, you can just feel it in your fingertips… I don’t know what you can feel, exactly. It’s an energy, an excitement.’ The connections between humankind and wood, he points out, go back a very long way: it is one of the very oldest raw materials. For him, wood is ‘almost like a nervous system.’

He enjoys working with bright, saturated colours of acrylic, which he spray-paints onto sections of his wooden sculptures in thick layers. The smooth, glowing surface provides a striking contrast with the darker grain of the wood with its intricate patterns. The ‘vibrancy’, he says, also takes him back to his childhood in the Caribbean. ‘The land is so fertile there – things just grow.’ Sitting on his desk is an early free-form sculpture in tulip wood, lightly sandblasted and partly sprayed in pale pink, which represents an abstract version of a sewing machine, in tribute to T. Michael, a Norwegian friend who is a fashion designer.

Baugh smiles mischievously as he recounts how he met Angel Monzon, creative director of Vessel Gallery, for the first time. A few years ago, he happened to be in Notting Hill, walking past the gallery, when he made the decision to go inside and talk to Monzon. At the time, only one wooden object was on display. ‘It was the first time I had walked into a gallery and enquired about the possibility of doing a show,’ Baugh recalls. ‘Angel was helpful and gave me good advice. Part of me thought that we would end up doing a show together one day.’ This year’s Collect featured an unusually large number of wooden sculptures. Not long after the fair, Baugh received an invitation from Monzon to send him some work – and the rest is history.

When I ask Baugh if wood is ‘having a moment’, he argues that it is more than that. ‘I think it’s here to stay,’ he says. ‘I think more people will turn to it. It’s the most natural material. Everyone relates to it.’

The artist at work | Photo © Alun Callender

The present exhibition intentionally coincides with Black History Month. It shows a collection of vessel-like sculptures based on Baugh’s reflections during the pandemic, although the first such vessel he made was finished just before the first lockdown. One of the most striking pieces from this collection is Zurri 0.1, a sand-blasted vase in tulip wood with an exaggerated curling lip that has been spray-painted bright orange, while the side of the vase has been carved with runic designs reminiscent of the traditional facial markings found in parts of sub-Saharan Africa. This sculpture is conceived as part of a collection of three vessel-shaped Zurri sculptures that will reflect on Baugh’s ancestry, which ultimately runs through the Caribbean back to Africa, and which he hopes to trace more precisely through a DNA test. As he puts it, ‘my Union Jack is one in the colours of Jamaica.’ In making Zurri, he began to realise that ‘indigenous people from around the world used the same tools, and you see a repetition of patterns’. He plans to explore this idea further elsewhere in the collection.

Also on display are three sculptures from his Masai series: long wooden statues suggesting human figures in the abstract. These sculptures represent a creative response to a myth told by the Kenyan tribe that their ancestors were once upon a time visited by giants with enormous heads; they also recall the colossal heads of the Olmec civilisation discovered in Mexico. Baugh’s eventual aim is to make a substantial collection of them to put in an installation. ‘They’re getting taller and taller,’ he says. In the future he also plans to make a more ‘figurative’ collection based on the female form.

In 2024, Baugh’s career as a sculptor in wood is well on its way: he already has several exhibitions in the pipeline for the coming year, including one in Venice. He is also planning to do a show with glass and metal artist Chris Day (also represented by Vessel), of Jamaican descent on his father’s side, and ceramist Chris Bramble, whose work draws on Zimbabwean traditions. Baugh’s interest in his heritage can be seen in The Chair of Uncomfortable Truths (2023), which reflects on the slave trade, including the major role played in it by religion. The ‘Chair’ is designed for two people to sit together back-to-back. If you do this with a stranger, Baugh says, ‘there’s an element of uncomfortableness’. Its design, complete with nails, chains and crossbar, evokes a crucifixion, and also reflects on the way in which slaves in the marketplace were treated as mere chattels. It is accompanied by a commemorative poem by the writer Komali Scott-Jones.

Baugh describes himself as ‘a dreamer’ who is always thinking up new ideas. ‘If I won the lottery,’ he says, ‘I would invest it in the best workshop and facilities, and in travelling to learn about other crafts.’ He hopes one day to make a sculpture in which an external form is repeated within the interior, ‘like a Russian doll’, and to develop a technique for sandblasting, ‘so that the wood is nearly transparent and you can see its veins.’ Wherever he goes next, the imaginative and beautifully executed works he has produced so far demonstrate the true originality of Donald Baugh as an artist, and the strength of wood as a medium for sculpture.

AKANSA solo exhibition 1 - 31 October 2024

Further Works by the artist

Uhuru 0.3

Unique | Ash | H 60 cm W 35 cm D 9 cm

Photo © Agata Pec

Umama 0.1

Unique | Ash | H 151 cm W 47 cm D 27 cm

Photo © Violeta Sofia

Masai 0.1

Unique | Sapele | H 89 cm W 28 cm D 9cm

Photo © Agata Pec

Zurri 0.1

Unique | Tulip Wood | H 56 cm W 35 cm D 17 cm

Photo © Violeta Sofia

Kakra 0.2

Unique | Tulip Wood | H 48 cm W 23 cm D 13 cm

Photo © Agata Pec