A Sculptor with Consummate Skill | An essay on Elliot Walker by Emma Park | For Urban Glass

3rd August 2021

A Sculptor with Consummate Skill

With his triumph in the second season of Blown Away, Elliot Walker proved his technical mastery, yet the British glassblower refuses to make functional glass | An essay by Emma Park for the Glass Quarterly issue No 163 - Summer 2021Ask any British glass artist today to name a rising star in their field, and the unhesitating answer will likely be Elliot Walker. The success of the “random Brit” of Blown Away has brought him greater publicity, but no one can say it wasn’t deserved. “Technically, he’s a maverick,” says Angel Monzon, creative director of Vessel Gallery, which represents Walker. “We haven’t had a sculptor of this caliber in this country for a long, long time.” This view is shared by Peter Layton, the elder statesman of Studio Glass in Britain and founder of London Glassblowing, where Walker worked for eight years. “He’s a brilliant craftsman … I don’t have his skills, never will have.”

For his part, Walker tells me, he has deliberately sought “practical skill” in glass, not for its own sake so much as because, in his view, this is the single most important attribute of a good glass artist. “You have to understand the skills, because if you don’t, then you don’t know what you can do with the material.” In other words, he seeks facility in the language of glass in order to use it for artistic expression. In the U.K., glass is still usually lumped with design, decorative arts, or crafts rather than being considered a fine art. But as far as Walker is concerned, he is as much a sculptor as any maker of bronzes—who, he points out, actually works in clay and has to send pieces off to a foundry to get them cast.

The Blown Away champion has made a name for himself not just for his technique but for the freshness and independent spirit of his works. At London Glassblowing they speak of his creativity and playfulness while Layton in particular highlights his “enormous initiative, enormous drive, incredible energy.” For Monzon, there is a “rock-and-roll” air to his works, almost an over-burgeoning enthusiasm; in some cases, the gallerist suggests, he still needs to “step back a little bit and edit himself.”

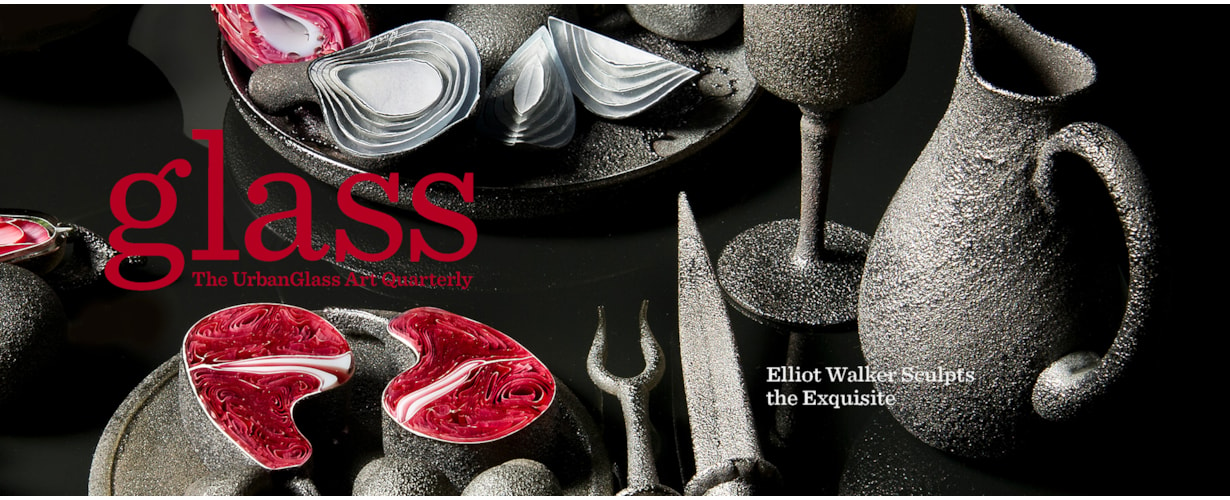

Above; The Banquet, (detail) 2017. A unique installation on display in Vessel Gallery depicting an abundant feast laden with delicacies and domestic items. Individual elements can be used to create smaller still-life settings. Table dimensions: H 170 cm W 70 cm D 70 cm | H 27 ½, D 27 ½, L 67 in.

Walker certainly has a rebellious streak, an ability to make things in glass that generate cognitive dissonance because they are at once beautifully executed and slightly disturbing. For instance, his contribution to London Glassblowing’s post-lockdown exhibition “New Horizons” includes a selection of hot-sculpted pieces of sushi, around 3 to 5 inches high, with pristine white rice balls, gelatinous orange fish roe, glowing green cucumber, and curling purple prawn tails. The pieces capture the elegance of the Japanese aesthetic; at the same time, the experience of seeing an inedible, tasteless material in the form of enticing mouthfuls of seafood—only heavier and larger than life—is disorienting.

One thing Walker is emphatically not, and that is a maker of functional vessels. “People still ask me, ‘Oh, can you make me a decanter?’ and it’s like, ‘I’m sorry—no!’ I make a decanter, but then I put it into a sculpture.” For his recent solo exhibition “Plenty,” held online with Messums Wiltshire, he taught himself the technique of reticello to make a series of Venetian goblets, purely so that he could then half-crush them between two huge blocks of concrete or brass. In these sculptures, under the title of Corruptioin (sic), the distortion of form suggests the effect of “the pressure of the technique and the pressure of the history” on the glass artist. The pieces also demonstrate Walker’s obsession with finding the right technique for the work rather than suiting the work to the technique. “I hate canework, I really hate it,” he says with feeling. “It’s so lengthy and so much goes wrong, and it’s really hard, but I had to do it to be able to create the piece that I wanted.”

Hiring space for a hot shop in the U.K. is prohibitively expensive, and artists end up in the most unlikely places. Walker’s studio is in Hertford, just north of London, tucked in between a line of warehouses selling car tires, industrial machinery, and bathroom appliances. He and his partner, the glass artist Bethany Wood, rent one half; the other is occupied by Simon Moore, the former creative director of Salviati.

Left; Irreverance, 2020. Blown, sculpted glass, forged silver. H 11 ¾ (each), W 4 ¾, D 1 ½ in.

Right; The artist with studio assistant and fellow artist Bethany Wood.

With his beard, shaved head, and ear and lip studs, Walker gives off something of a “bad boy” vibe at first glance. He speaks with a gentle Midlands twang, now familiar to fans of Blown Away, that reflects his upbringing in a village near Wolverhampton. Not far away from Wolverhampton is the town of Stourbridge, one of the historic centres of England’s glass industry since the 1600s, when James I banned the use of wood in furnaces and so pushed glass production to areas with easy access to coal. In this region there is also a centuries-old culture of independent artisans, free-thinking, self-sufficient, and self-taught. In some sense, Walker is a descendent of both these traditions.

His first encounter with glassmaking was in the summer after leaving high school, when he attended a night course on stained glass. He then went to Bangor University, in remote north Wales, to study psychology. However, he carried on making stained glass in his spare time, for commissions and craft fairs, and attended courses on lost-wax casting and kilnforming during the holidays.

While he would soon abandon any thought of a career in psychology, his education in this science has influenced his artwork. This can be seen, for instance, in Spilt Milk, a carton of milk in clear glass with a touch of opaque white at the bottom, a glass on its side, and a puddle of milk that has spilled out of it. It was made for Blown Away Episode 7, where the task was to reflect on “a personal hurdle” that competitors had overcome. The piece was disparaged by the judges as “a little bit generic” and not sufficiently “personal”; possibly something was lost in translation between British and American forms of self-expression.

In any event, Walker insists, he was trying to make a serious point. “When I was studying psychology, the idea of acceptance and commitment therapy was something that I really wanted to go into; it’s a Buddhist philosophy of separating yourself from your emotions entirely.” The concrete representation of an old proverb was intended to allude to this psychological detachment, the idea of “releasing an emotional hold that an event has on you.” Spilt Milk is deceptively simple. The limpidity of the glass is aesthetically pleasing, but at the same time the transparency of the bottle hints at the importance of mental clarity and detachment from one’s problems, represented by the cloudy milk. The title, like many of Walker’s, is playfully ironic but also an integral part of the work as a whole. “The title and the signature, that finishes a piece off.”

After his degree, Walker made the decision to practise glass full-time and enrolled at the International Glass Centre in Dudley, north of Stourbridge. Part of the Dudley College of Technology, the IGC was originally set up to provide vocational training to support the local glass industry, but it closed down in 2009, just after Walker applied. He was able to spend a year as an associate at a new course set up on much smaller premises, where he worked with little supervision. “I was coming in whenever I wanted and messing with the kilns, turning the furnaces on, setting the layers, and messing around with all this stuff that I really shouldn’t have been allowed to mess around with.”

In the wake of the financial crisis, and with tuition fees increasing, the next decade would be a difficult time for glass at British universities. When Walker moved on to study for an MA in Glass at the University of Wolverhampton the following year, he found that the formerly skills-based course, part of the region’s declining glass industry, was being merged with applied art and design, and little education was provided—either academic or technical. “I struggled a lot,” he recalls. Paradoxically, however, this informality gave him the freedom to pursue his own ideas and experiment. He often worked in partnership with another student, Tim Boswell, whom he had first met at Dudley. “He would have an idea that, you know, neither of us really could do. And so we’d have to try and do it together.” He also benefited from the expertise of the technician Simon Eccles. When no classes in a particular technique were available, Walker would often teach himself by watching YouTube videos.

At the end of his MA, Walker was demonstrating with Boswell at Art in Action, an arts and crafts festival in Oxfordshire, when he was talent-spotted by staff from London Glassblowing, who offered him a job as an assistant. It was a crucial step in his career. Peter Layton’s studio has become a sort of Renaissance master’s atelier, or, as resident artist Louis Thompson describes it, a “creative hub.” While other institutions offer teaching, London Glassblowing, according to Walker, is practically the only place in the U.K. where a community of practitioners, who are all glass artists in their own right, can meet and work together, with Layton “constantly feeding ideas and techniques.” Nearly all of the country’s leading glass artists have spent time there, from Colin Reid to Cathryn Shilling. Working with other artists gave Walker new “creative momentum,” according to Layton, while his own supervision challenged his assistant to reflect on what he was making and how to present it, as well as necessary business knowledge, such as the quality and price required of glass capable of being sold professionally.

Walker was always looking for opportunities to work on his own projects and with new artists and makers, first at the weekends and then over longer periods, for which he rented studio space outside London, in the Midlands or Wiltshire. Another key stage in his development in the last four years has been his relationship with Vessel Gallery and Angel Monzon. Looking back on the artists he has supported, Monzon says, “Elliot has always been at the forefront for me.” He has helped to refine aspects of Walker’s presentation. In the latter’s series of exquisite pieces of cut fruit, Still Life, inspiration for which he drew from Dutch still life paintings, it was Monzon who suggested that the pieces be grouped together and displayed on acrylic plinths, each with their signature and individual title.

Above; Citrus Sinensis (from the “Still Lives” series), 2015. Blown glass with hot-sculpted, cut and polished fruit. H 9 ¾, W 15 ¾, D 11 ¾ in.

In 2017, Vessel hosted Walker’s second solo show, “Half-Life.” By his own reckoning, he spent about a “year and a half” working on it. Monzon again helped with the selection process: “There was a lot of editing … You can’t just throw something in for the sake of throwing something in. It needs to work.” The show was held in Vessel’s basement gallery, which Walker painted completely black. Inspired by debates about denuclearisation, he set out some of his trademark fruits, with charred, textured, black or white surfaces, in an apocalyptic banquet. He also hit on the idea of using uranium glass to sculpt the “aftermath” of objects exposed to radiation: small chairs, a teddy bear, children’s building blocks, flowers, and a human skull.

Uranium glass is the most expensive material he has worked with. When it was still made in the U.K., he says, the manufacturer had to have “a fire engine on site because of the volatility of the material.” In the exhibition, he shone ultraviolet light on the artefacts, which made them glow yellowish green. “If you imagine an apocalyptic world, it’s like the work is frozen in time,” says Monzon. “It’s like everything’s been vitrified … It was haunting to go into this black room and have these little glowing sculptures, these pieces that looked like children’s toys.” While he was making the exhibits, Walker placed them around his flat. He describes how, caught by the evening sun, they were transformed into something “otherworldly.”

Above; Artefact Aftermath, installation from the “Half-Life” exhibition at Vessel Gallery in 2017.

Walker’s growing reputation as an artist has enabled him and Wood to work increasingly for themselves. Last year, Wood set up Blowfish Glass, an online gallery that sells works by both of them as well as by other up-and-coming glass artists. The couple work closely together. “We hardly ever need anyone else,” Walker says. “We’ve worked it out so we can do everything we need to do, really complex work, just with the two of us.” They are now hoping to move back to the Midlands, perhaps to set up studio at the Red House Cone, a hot shop and demonstration center in Stourbridge’s Glass Quarter. Walker is keen to start working again in front of an audience, as he did at London Glassblowing, where the studio is open to the public. “I actually prefer making with people watching,” he explains; this love of performance doubtless made it easier for him to keep his cool on Blown Away. The residency at The Corning Museum of Glass, part of the prize for the show, is something he plans to take up soon, assuming travel restrictions are lifted.

In artistic terms, Walker’s long-term ambition is to produce larger-scale projects, like Bodge Job, his winning installation in the show’s finale. But a challenge for a glass artist, especially in Britain, is always going to be finding the funds for such projects. As Layton puts it, looking back on 50 years of making glass, conditions over there are “constricting” compared with the U.S. “Our customers don’t have sufficiently big pockets or big houses.” Monzon’s experience as a gallerist is similar: “I don’t think we have a single million-dollar collection in this country.”

For his part, Walker is frustrated with what he sees as a “gallery bias” against his material. “I’ve had a lot of galleries I’ve been in touch with, and they’re like, ‘We’re sorry, we don’t deal with glass.’” As exemplified by his own sculptures, glass art in the U.K. is taking a more conceptual turn at the moment, but public tastes are taking a while to catch up. In the last two or three years, however, there have been signs that this is changing. A virtuous effect of the pandemic has been to force galleries and exhibitions to display ever more of their works online; this has opened up British glass to an international audience.

In the past, Walker had maintained a steady income stream from lighting commissions for the Contemporary Chandelier Company. He has always been determined, he says, to avoid being absorbed by a big design company––although this has been less of a concern since his success on Blown Away, which has brought a spike in gallery purchases. He is still intrigued by the integration of glass sculptures into furniture, the “weird, vague area” between art and design.

The area between art and design is something which he explored in his Corruptioin pieces for the Messums show. The latter also incorporated what he refers to as his “grotesque massive fruits”: three blown and mirrored sculptures, like gigantic versions of Venetian table fruit but with a touch of Koonsian vulgarity in their shiny surfaces and exaggerated dimensions. Their titles, Orbsurdity, Obeseberry, and Plumbp, satirise consumer excess. A further series of still lifes in the same show, called Bleach, consists of sparkling arrangements of lobsters, seaweed, and coral, as if intended for centrepieces at a dinner party. The shimmering transparent glass in which they are made, however, chillingly reminds us that the reefs are being killed by pollution.

Although aware of the challenges he faces as a glass artist, Walker is prepared to play the long game. “The work that I actually want to make will take me another 10 years to actually get to grips with and build up the funds for.” He is currently mulling over further projects on an environmental theme, including the treatment of nuclear waste. “They vitrify the waste to make it safe, then they shove it into big lead rockets and drop them into the sea.” Nukes in glass? Absurd. But when he puts it like that, it sounds just right: the vision of an artist who thinks in and beyond his medium. We look forward to the next episode.

Frequent contributor Emma Park is a London-based arts writer and podcaster with a focus on the fine arts, classics, and education.

Further artworks by Elliot Walker | Bethany Wood | Louis Thompson | Simon Moore

Left; Irradiant Bloom III, 2017. Iridescent and black glass. H 31 ½, W 21 ¼, D 3 ½ in.

Right; Bleach 1, 2020. Blown, sculpted glass, MDF, PVC , acrylic. H 14, W 15 ¾, D 15 in.